Bladder Stones in Dogs

Bladder or urinary stones are called uroliths or calculi, and are rock-like collections of minerals that form in the bladder. Minerals that may be involved include magnesium ammonium phosphate, calcium oxalate, urates, and others. There may be a single stone, a few, or many, the size of grains of sand.

Urolithiasis (the formation of urinary stones) is a common condition responsible for lower urinary tract disease in dogs and cats.

Why do uroliths form?

Uroliths form when the urine is oversaturated with minerals, and there are several factors that can lead to the formation of uroliths.

Diet, metabolic illness, genetic factors, and bacterial infections of the urinary tract can predispose to urolith formation. While the exact mechanism is not known, high dietary intake of minerals and protein in association with highly concentrated urine may contribute to increased saturation of salts in the urine. Disease conditions such as bacterial infections in the urinary tract can also increase urine salt concentration.

There are several different types of urolith with struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) calculi and oxalate (calcium oxalate) calculi the most common. Since different types require different treatment, it is important to determine the type present.

What problems do bladder stones cause?

Most bladder stones are located in the urinary bladder or urethra. Urinary stones can damage the lining of the urinary tract causing inflammation. This inflammatory reaction may predispose the animal to bacterial urinary tract infection (UTI). Urinary stones may physically block the urine flow causing urinary obstruction that requires immediate emergency treatment.

Small urinary stones may become lodged in the urethra, particularly in male dogs, causing an obstruction that requires urgent treatment. Stones may also become lodged in the ureter (the portion of the urinary tract carrying urine from the kidney to the urinary bladder) also causing an obstruction that results in serious kidney damage.

What are the clinical signs?

The two most common signs of uroliths are blood in the urine (haematuria) and straining to urinate (dysuria). Mechanical irritation of the lining of the bladder and lower urinary tract causes bleeding, inflammation, and pain.

Dogs may also urinate small amounts frequently, sometimes only passing a few drops at a time, and can urinate in inappropriate places such as in the middle of the kitchen floor.

Stones can also block urine passage. The dog may be straining to urinate without passing any urine. It may be depressed, stop eating and start vomiting. Emergency veterinary attention is required.

How are bladder stones diagnosed?

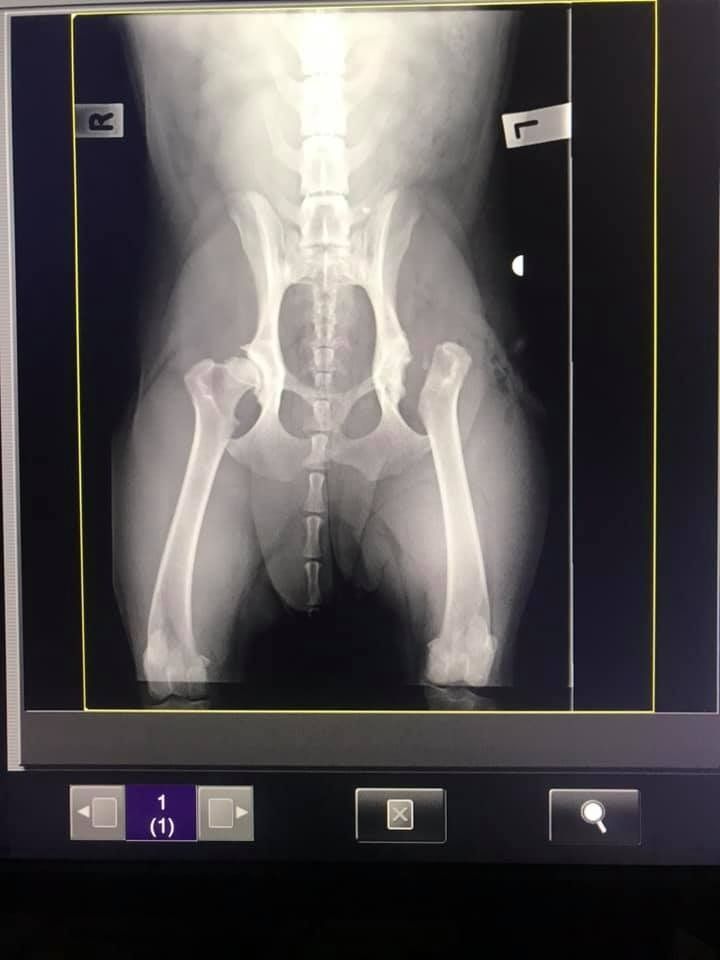

Some large stones can be palpated through the abdominal wall, but radiographs are required to diagnose their presence. Some stones are not directly visible on radiographs and air and/or dye must be injected into the bladder to visualize them. Ultrasound examination will also detect uroliths.

Blood and urine tests will also be taken to investigate the condition and determine the best method of treatment.

How are bladder stones treated?

Struvite stones may be dissolved medically by feeding a commercial prescription diet. The diet must be fed exclusively and the process can take up to a few months.

However, calcium oxalate, urate, cystine and silicate stones cannot be dissolved and require surgical treatment. There are many factors that influence the best approach to treatment.

Antibiotics are used for any bacterial infection.

Do bladder stones recur, and can they be prevented?

The recurrence rate is 20% to 50%, so preventative therapy is important. Ongoing medication or a change in diet may be recommended, depending on the type of urolith present.

Commercially prepared diets are recommended to reduce the risk of recurrence/occurrence of struvite and calcium oxalate urolithiasis. These diets control the urine pH and contain reduced levels of protein, magnesium and phosphorus to help limit the building blocks of crystals and bladder stones.

By Provet Resident Vet

Contributors: Dr Rebecca Bragg BVSc, Dr Julia Adams BVSc